The Effects of Brown vs. The Board of Education in Montgomery County

Reactions

County police on hand at the end of the first day of school, Poolesville High School, September 1956. © 1956, The Washington Post. Photo by Jim McNamara. Reprinted with permission.

In 1954, the population of Montgomery County was only 6% black, with the majority living in long-established communities up-county. While World War II had brought a large influx of new residents, there was still a Southern sensibility in the rural areas. Although tempered by common sense and a reluctance to go against the laws of the land, there appears to have been a general feeling against integration among much of the county’s white population. Yet on the whole, Montgomery County’s school integration was felt to have gone fairly smoothly, particularly when compared with many school districts in the south, where protests, demonstrations and even violence were a problem.

In our county, while feelings were decidedly mixed on the part of white and black students, parents and teachers alike, only a few schools registered official complaint with the Board. However, racism was in some instances strong enough to change Board policy. The original plan to integrate the black schools, as well as the white, was never realized; only Taylor, one of the consolidated elementary schools, was ever used as an integrated school. Plans to use Carver, a large and modern high school built in 1950, fell apart after some parents refused to allow their children to use equipment that had belonged to black students. Carver and the rest of the modern black schools were turned into special education centers, offices or storage.

As in everything, the experiences of students and teachers varied from individual to individual, and from school to school. In some cases, a cautious transition period was all that was needed to calm tensions and fears (on everyone’s part). Some black students recall being asked strange and even insulting questions by their white classmates, but they feel also that these were asked out of genuine curiosity and ignorance, not maliciousness. On the other hand, some students knew exactly what they were doing; Poolesville High School, in particular, was the scene of many pranks and fights that first year, although the administrators and teachers did what they could to calm things down.

Adults weren’t always much better. Some teachers felt welcomed into their new schools, but others had problems adjusting to an initially hostile environment. The continued segregation of the rest of Montgomery County caused problems outside of school. Integrated faculties couldn’t necessarily have meetings in restaurants, and student hangout spots – swimming pools, for example, or Glen Echo Amusement Park – were off-limits to new, mixed groups of friends.

Some black teachers found themselves demoted when transferred to an all-white school. The NAACP protested the Board’s vague policy on personnel, and many teachers were concerned about losing their jobs. However, most teachers appear to have kept employment with MCPS.

In March, 1956, the Gaithersburg PTA passed a resolution against “compulsory integration,” which was being forced on them “in disregard of traditions, customs and feelings that have prevailed for generations, and still prevail.” The document stated that the PTA was “firmly opposed to the compulsory and forced integration of races [in the Montgomery County Public Schools] and to the assignment of Negro teachers to white children whose parents object,” claiming, among other objections, that “county-wide tests of children in the public schools disclosed that approximately 90% of the Negro pupils were below normal,” and that “except for a small group of agitators, the great majority” of blacks in the county “have no desire to become the supposed beneficiaries, or victims, of compulsory integration” and are “seriously disturbed and fearful of the adverse effects that hasty and compulsory integration could have upon the emotional and psychological well-being of their children and upon the good relations presently existing between the races in this county.” Apparently no further action was taken in this case, as Gaithersburg schools later integrated with few reported problems.

The PTA at Rollingwood Elementary School, in Chevy Chase, wrote to the Board in 1955 protesting the proposed transfer of students from the black Linden School, in Forest Glen. The white schools nearest Linden could not take additional students until building expansions were completed; Rollingwood had room. Claiming that a switch from Linden to Rollingwood and then to yet another school would be too confusing for the Linden students, the PTA also expressed their unwillingness to mix their own children with students from another race or economic class. They suggested that Linden remain open for another year while nearby white schools completed their additions. Superintendent Norris refused this suggestion, pointing out that the Linden building had in fact been condemned. Parents from Rollingwood protested at the State Board of Education, which ruled in favor of Norris.

Linden School, Forest Glen, 1930s. This school, sometimes known as Lyttonsville, opened in May, 1889. The building shown here was originally a portable at B-CC high school, moved to Linden in 1931 to house Linden’s black students. It was one of the four remaining “substandard schools” that were closed in 1955 as one of the first steps in the county’s desegregation.

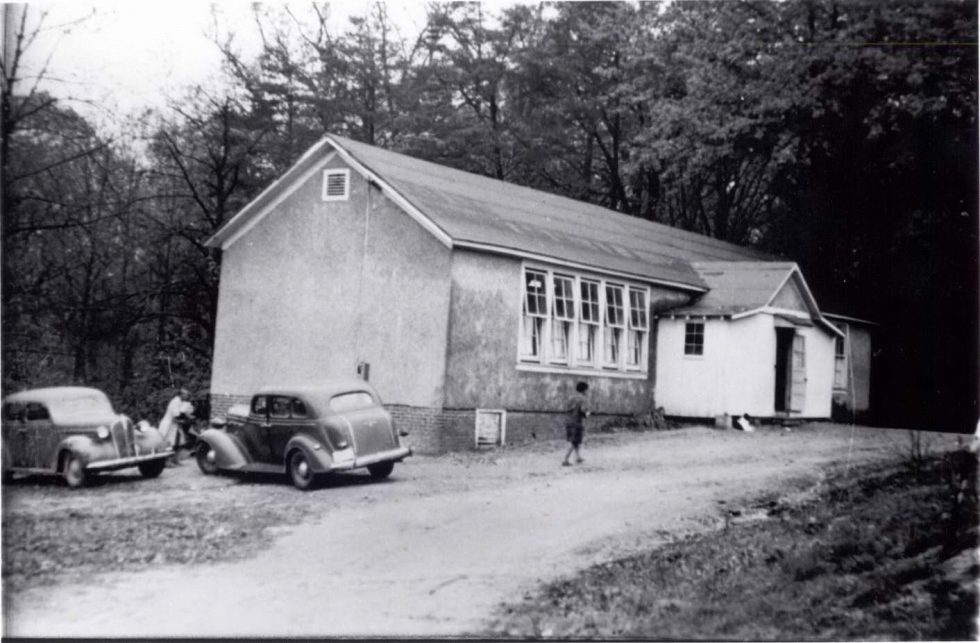

The school district that faced the most opposition to integration was Poolesville. At that time, the white community was so small that all grades, kindergarten through 12, attended the same school. When integration came in the fall of 1956, there were letters, meetings, and a demonstration outside the Board of Education by angry white parents. On the first day of school, some 200 of these parents stood outside the door, hoping to prevent the 14 black students from entering, and threatening to remove their own children from school. Police and Superintendent Norris were on hand, and they escorted the black students in through a back door. Some parents did remove their children, but Norris threatened to take them to court, and they backed down. Although the feelings and fears were already there, many people thought that the actions taken were incited by outside influences, namely segregationists from the South who arrived hoping to stir up trouble. Within a week or two, the agitation had subsided, and the rest of the year progressed with relative quiet.